“The Game” that Changed Baseball—Part I

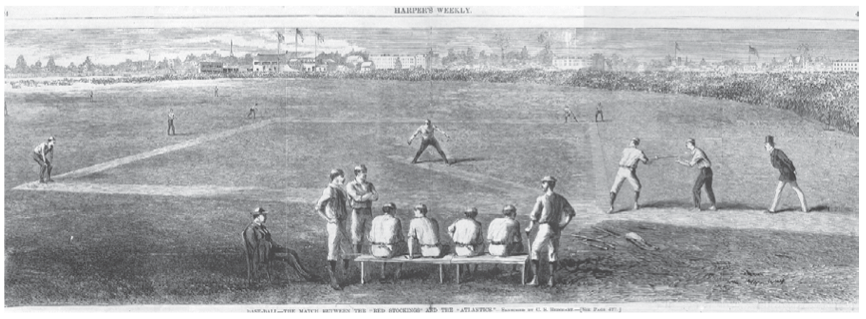

The first important professional baseball game was not part of a World Series, or any series for that matter, it was one game played at the Capitoline Grounds in Brooklyn, New York, on a warm June afternoon in 1870 between two of the finest professional squads in the country.

The game was a catalyst, setting a fire under a series of changes already overwhelming amateur and nascent professional baseball. The shape of professional baseball would change after this game. And not because the game disappointed in any way but because it helped refine the notion of what professional baseball was, beginning in Cincinnati, Ohio, only a few weeks after the game was played.

Before the game, professional baseball had meant one thing, and it would mean something else after. Of course, fans, players and ownership today understand what this meaning is, but back in 1870, the definitions of what a professional baseball team was, rather than an amateur team, were still being ironed out.

During the 1869 baseball season, the Cincinnati Red Stockings were a perfect 57-0. This was not the result of good fortune or daily prayer. Some of the Red Stockings’ 1869 statistics read like these: George Wright, star shortstop of the team, batted .633 with 49 home runs and scored 339 runs in the team’s 57 games. That’s about six runs a game. The team as a whole, over 57 games, scored 2,396 runs and allowed only 574. Meaning that the average score of Cincinnati’s victories was 42-10. Impressive, even for 1869.

The team planned its 1870 schedule with a trip East in June to play the best professional teams in the country. Upon arriving in New York, Cincinnati was scheduled to play Boss Tweed’s professional squad, the New York Mutuals, perhaps the most crooked baseball team in the nation, egged on by its Tammany Hall owners. And that was saying something in an era when gambling was so prevalent it effected the way baseball was played.

All 10 members of the Red Stockings found their way to the Grand Central Hotel on Broadway and East Third Street, where the team stayed while in New York. Among players on the tour was the team’s great pitcher, Asa Brainard; its well-groomed and mutton-chopped manager, centerfielder and sometimes relief pitcher, the Englishman Harry Wright; and its great shortstop, George Wright, Harry’s younger brother. It was a formidable squad.

A few days later, the team crossed the East River into Brooklyn, and a couple of miles in found themselves in South Williamsburg at Marcy Avenue and Rutledge Street, the main entrance to the completely enclosed Union Grounds, home of the New York Mutuals (and several other local baseball teams).

The game was played without interruption, despite the ravenous entreaties of the Tammany Boss William Tweed, who tried several times to convince Harry Wright to throw the game in the Mutuals’ favor, presumably for a fortune of money. But Harry Wright and his players would have none of it.

Harry Wright played baseball games to win. And only to win.

And that’s what Cincinnati did. They bludgeoned the Mutuals 16-3, in a game that was not even as close as the score. The Red Stockings were now 27-0 for the season.

Almost immediately after the victory, the sporting press and the gambling community came out with bold predictions that Cincinnati would not lose again, predicting 1870 would be another perfect season. The gambling community was actively soliciting bets for the Brooklyn Atlantics’ game with Cincinnati 24 hours later.

June 14, 1870. Cincinnati crossed the East River again, headed to the Bedford Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn where the Atlantics played their home games at the Capitoline Grounds, a sprawling field that splayed across Halsey Street and Putnam Avenue on one side, and Marcy and Nostrand Avenues on the other.

The New York World set the scene this way:

“Little urchins shouted, ‘score cards, names and positions of both nines,’ all the way from Fulton Ferry to Bedford, and all Brooklyn seemed awake to the event of the day. Stores were deserted, boys who could not obtain permission to leave school played hooky, and hundreds who could or would not produce the necessary fifty-cent stamp for admission looked on through cracks in the fence, or even climbed boldly to the top, while others were perched in the topmost limbs of the trees, or on the roofs of surrounding houses.”

So, to say the game had been well-publicized the past weeks does not say enough about the anticipation and sheer excitement of “The Game.” And that’s why 20,000 overzealous Brooklyn fans paid $.50 each to jam onto the grounds. The attendance estimate was a record for that time. What there was no doubt about was that fervent anticipation scented the early afternoon air. Fans were camped everywhere they could around the field, even on the edges of fair territory, which was allowed. All of them eagerly awaiting the first pitch and the chance for the Atlantics to avenge their 32-10 defeat to Cincinnati the year before in Ohio.

Coming up in Part II: The Game