The Game that Changed Baseball—Part III

This is the final installment of a three-part series. See Part I, Part II

This is the final installment of a three-part series. See Part I, Part II

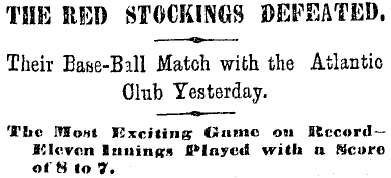

Writing in his baseball column the next day, Henry Chadwick gushed about the wildly entertaining game. He was not the only one. The New York Times called it “the most exciting game on record.” But, The Times also was critical of the crowd, calling them “The most discreditable gathering we have seen at the Capitoline Grounds in years.” Referring to the Brooklyn fans, the New York Sun described them as “escaped lunatics.”

The press concluded they had witnessed not only the brilliance of professional baseball, but perhaps the finest game ever played.

What happened next was unexpected and, given the growth of baseball as a business people would pay to see, ludicrous.

Back in Cincinnati

When Harry Wright and his Red Stockings returned home, the president of the Reds, Aaron Champion, had already issued a public apology for the dishonor his club had brought to Cincinnati.

The irony of the apology was that his team had only been proven human. They lost a game. Champion apologized because Cincinnati believed their Red Stockings would never have suffered even one defeat. Why think that? So, the immediate question in Cincinnati was, what good was a professional baseball team that lost games?

But it would not be answered the next season.

Champion and many of the wealthy patrons who had financially supported the team no longer wanted to sponsor the outrageous salaries of losers. Suddenly, spending so much money seemed sinful, as if they were paying mammon for civic pleasure.

The Red Stockings, once a source of civic pride and joy, had become an embarrassment. So, when Aaron Champion met privately with Wright, he leaned back in his plush maroon-leather desk chair, his thumbs tucked into the pockets of his silk vest as his elbows jutted out from his rotund body, and said, “You lost the fucking game Harry. I still can’t believe you blew it. What the hell happened? I thought you were this brilliant baseball man.”

Wright laughed, lit one of the cigars Champion had offered, and spoke slowly, quietly, in his regal British accent, “It was one of the most exciting games this year. They sold more than twenty thousand bloody tickets for $.50, they could’ve sold two or three times as many, there were that many people outside the grounds, but they didn’t have space. It was baseball at its best.”

Champion threw his feet on the top of his oak desk and crossed his legs before he barked, “What about your fucking brother?”

“What about George?”

The banker slid a gold watch out of his vest pocket and wound it as Wright adjusted the lapels of his own three-piece plaid suit glaring at the banker.

“We’re professionals Aaron. Players. And players make errors occasionally. George’s a fine player. He’s not the reason we lost. I am.”

“Bullshit,” the banker pulled on his cigar and then blew a precise ring of smoke into the air toward the gilded ceiling that diffused out across the dark molding running around the edges of the walls. “Little Georgie cost me $1400 dollars this year, and the fucking game.”

Wright rose from the plush leather chair, sucked on the cigar, circled the large room, before he stopped in front of Champion, blew out a ring of smoke, and snapped, “You’re goddamn wrong. The bloody games are worth seeing. Period. No one wanted their $.50 cents back.”

“You don’t say?”

“A good game’s worth $.50 cents; a poor one’s dear at $.25. As long as the product’s exciting and takes the public’s mind off the drudgery of their lives, people’ll pay $.50 cents. Errors or no errors.”

Champion studied Wright as if just for a second his manager had made sense. “You really think so?”

“Absolutely.” Wright said, puffing on the cigar he was smoking. “The business of baseball’s about winning, right? And winning costs money.”

“We’ve paid you enough money already.”

Wright smirked.

“We made $1.39 this lousy year. That’s our entire goddamn profit.”

“You’ve got to build the bloody game, establish a league,” Wright went on, “to make the bloody game work. It’s like a cow, you can milk it. But you have to feed it. Care for it. Get it, mate?”

“We’ve decided to rip down the stadium. Sell off the pine. Should generate enough money to pay off all our creditors. And your salaries.”

“Good for you.”

“I’m sorry Harry. You can work for us here at the bank if you’ve nothing better to do.”

A New Beginning

A New Beginning

Wright didn’t answer. Instead he smiled. He already knew that he could take his best players, arrange for everyone to earn more money, and on that foundation build a championship team in the East. All he needed was a big-game pitcher to throw the important games. The best money could buy.

“What?” Champion said. “What are you thinking?”

Wright held the cigar and puffed some more, before he whispered, “It’s been nice working for you,” all the while remembering what his brother George had told him about a pitcher he’d faced several times, as he turned and left Champion’s office.

Walking through the ornate lobby he could hear his younger brother’s voice. “He’s the best bloody pitcher I’ve ever squared off against Harry, I swear.”

Wright stared at his brother before his eyes. Until he heard himself say, “The best?”

“He’s bloody unhittable when it matters. He shuts down rallies.”

“Who is he?”

“Uhm, Albert Goodwill Spalding.”

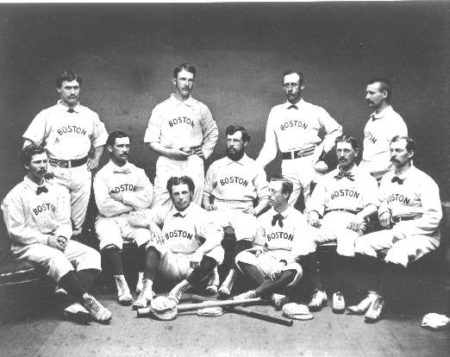

Within six months the Wright brothers, Charlie Gould and a few other Red Stockings joined the Boston Red Stockings along with Albert Spalding. They all agreed to lucrative salaries. Boston would be one of the first teams in the new National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP). And the best.

Boston would win the NABBP league championship four of the five seasons. They would even lose an occasional game, yet still be regaled as champions and professional baseball would never be the same again.

Until 1876, when the NABBP folded and its teams were swept up into the newly formed National League of Professional Baseball Clubs. The first solid, financially backed league (the same National League we know today). And the next wild west phase of baseball history would begin.