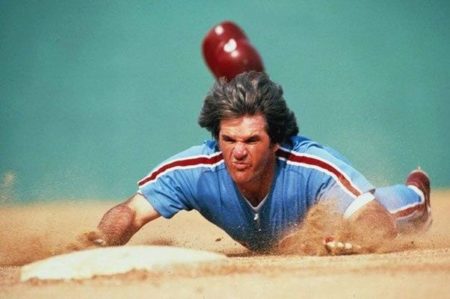

Where Have You Gone Charlie Hustle?

Baseball’s Issues

Baseball’s Issues

If you read Phil Mushnick’s column in the New York Post the other day, entitled, Machado shows baseball places value on all the wrong qualities, you read an astute analysis about what’s wrong with baseball. Mushnick writes that baseball has essentially become a slovenly, easy game. And while he does not explicitly mention money, it’s an important part of baseball’s fall from grace. Just as Charlie Hustle’s retirement still hurts.

Baseball and easy money have created the Manny Machado’s of today’s game. Player’s just waiting for their massive payday after their first six years in the bigs. As if numbers by themselves, even supported by analytics, demonstrate a repeatable skill set. Truth is, the numbers are not the whole story. While numbers might get a player into the Hall of Fame after 20 years, only truly great players win championships. Not their numbers. Here’s a short list.

Babe Ruth. Dizzy Dean. Joe DiMaggio. Yogi Berra. Mickey Mantle. Sandy Koufax. Jim Palmer. Tom Seaver. Reggie Jackson. Charlie Hustle. Cal Ripken Jr. Keith Hernandez. Paul O’Neill. Derek Jeter. Mariano Rivera. Pedro Martinez. Jason Varitek. Buster Posey. Madison Baumgartner. Jon Lester. And Mookie Betts.

Pretty good team. Ever think any of these players did not give it their best all the time? What about Charlie Hustle?

No matter their dedication and passion, every player—champion or loafer, All-Star or utility player—receives a salary. And in baseball, that means a large paycheck.

Players understand compensation is not only a reward for past excellence, but a motivator for future performance and, in a way, a ranking system of quality. A way of understanding their position in the pecking order of the best players in the game. Theoretically, only the best should rise to the top, like cream.

But in baseball, that’s not always the case. A player’s years of service affect his compensation through the early years of arbitration numbers that are no longer a reliable metric for the future.

Albert Pujols comes to mind, as does Robinson Cano, just jettisoned by Seattle, and Jacoby Ellsbury, whom the Yankees can’t give away.

Over the last five years, team management of all franchises has evaluated performance with a more critical eye, which is why older players have not been tendered contacts as often anymore.

The players see this, understand that baseball is awash in money for those who can justify an offer. How do they do that?

The Metier of Capital

Money is color-blind and only cares about replicating itself in the most efficient manner possible. It does not concern itself with the quality of the players or whatever else it might purchase. It just wants to make more money. And a lot of it.

But because of the disparities in player availability, teams have to make choices, hunches in a way, and hope the players they’ve offered contracts to justify those contracts. Even if in point of fact, most don’t. Despite analytics and the best guesses of front-office personnel. But the money has been invested and more than likely has already generated a return on investment even if the player does not pan out.

More season ticket holders. A rise in ticket prices for everyone else. More merchandising possibilities. And higher advertising rates because of the excitement generated by the addition of Jason Bay or Adrian Beltre to the team.

So, players have to show management they’re worthy of serious money. Maybe they’re such a great hitter that despite being a chronically weak defender, like Rhys Hoskins was in left field, the Phillies decided to move Carlos Santana to Seattle so they could redeploy Hoskins back to first base, the only position he can reasonably defend with any aplomb.

Or the player is solid, but not great, but because he can play multiple positions, and bunt, like Jurickson Profar, the team values his flexibility enough to pay him. Not like Manny Machado will be paid, but his compensation is still slightly over one million dollars in his first arbitration eligible season, and it will increase in January 2019 when he is tendered a second arbitration contract.

Or he’s a left-handed relief pitching specialist like Jerry Blevins, who is called upon to get out key lefty hitters in clutch moments.

And because money buys numbers, metrics, it rewards numerically superior accomplishments, not true quality. The player who does the little things that help win championships is ignored. This waters down the game somewhat by minimizing the commitment teams make to the end of their bench, despite the importance of that player to the team. So, players like Ronald Torreyes, recently a victim of baseball musical chairs, bouncing from the Yankees to the Cubs and then to Minnesota, where he may finally have found his next home, is a forgotten man. The Twins did not even offer Torreyes seven figures. Forget about nine. What this system of money insists on sensationalizing are the biggest stars like Machado, Bryce Harper, and anyone else about to receive big dollars, because that’s the easiest way to generate more return on investment.

The metier of capital.

Eyeing the Game from the Other Side

Fans either pay excessive ticket prices to see games in person, or watch on telecasts marred by professional broadcasters paid big dollars to parrot management’s position on team issues of the moment. Injuries. The upcoming schedule. This exciting series. Even what happened 47 years ago today when …

The other person in the booth is usually an ex-athlete, many of whom can barely form an English sentence as they bark out inept platitudes stuffed full of useless, meaningless stats. Ever listen to a Yankees telecast?

Or the almost untenable Detroit Tigers’ telecasts that will presumably, finally, change this season after their announcers physically clashed in public after a game at the tail end of the 2018 season, causing an uproar in Detroit. In truth, the Detroit broadcasts were difficult to listen to, especially the work of Rod Allen. Allen was the athlete in the booth and his comments were always off target, uninformed and, more often than not, non-sequiturs.

The owners coddle this endless money game. Telling their fans what to think (through their broadcasting megaphones) and then overcharging for their fans attention. How much better can it get for the owners? Where else can they find so much greenery growing wild on trees? Their ROI must be fatter than ever, though they’ll never admit it.

And Now the (Lack of) Hustle

Manny Machado is but the latest example (as was Robinson Cano and his newest teammate Yoenis Cespedes) of players who could not muster a hustle to first base. Players who believe they can play the game however they please. And why not? Has anyone in management ever disciplined them? Suspended them? Shown public displeasure? And in Machado’s case, he is yet one more pampered athlete who acts as if he’s invulnerable to criticism.

Apparently Buck Showalter, Machado’s only manager until he joined the Dodgers in July 2018, tried to instill a nascent baseball sensitivity into his talented upstart. Showalter would take him aside in the dugout and clubhouse for many one-on-one conversations, trying to communicate the idea of how baseball should be played. But, if this past season is any evidence, Showalter’s attempts failed.

In an opinion piece in the Washington Post entitled, Analytics, schmanalytics, Norman Chad wrote a humorous take on statistics in sports, commenting about loafers in baseball, that, “These guys only run hard to the bank.”

Well, Machado has begun to run harder this offseason, even after earning $16 million last year. (Enough for a lifetime for most people.) Because he can see another $16 million in his dreams.

And his dreams should come true. Why? Because management does not like to see talent go to waste. Even if it’s flawed. Unfortunately, there are no metrics for how hard a player can or should play.

And John McGraw and Ty Cobb are long dead. No longer able to set an example of inspired, passionate play. So, where are the examples of fiery passion in baseball? The answer is it’s not 1910 anymore. And Charlie Hustle retired more than a quarter of a century ago.

Bring Back Charlie Hustle

So, if a player doesn’t want to run a hard 90 feet to first base, the Commissioner has shown an unwillingness to address the issue. The feeling must be that as long as the fans don’t leave the stadium en masse in protest, or change channels, then if it ain’t broke, why fix it?

Maybe the Commissioner should run a Pete Rose seminar for Manny Machado and all the other players in the major and minor leagues to demonstrate the value of passionately caring about craft.

Perhaps Pete Rose would personally talk to every team in spring training? Not about gambling, please.

Rose was a breath of fresh air in 1963 when he literally burst onto the scene as a fresh faced rookie with endless spirit, unlimited hustle, and a fiery will to win. He was the Rookie of the Year that year.

Pete Rose. The role model that Manny Machado and many other in major league baseball today should be taught to emulate.

Bring back Charlie Hustle.

So Brandon Nimmo won’t feel so alone.