Hall of Fame Fantasies—from Jurickson Profar to Mariano Rivera

Cooperstown Dreams

Cooperstown Dreams

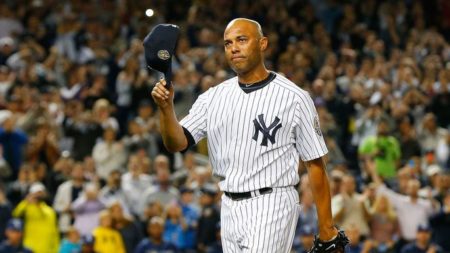

Every player has fantasies of being immortalized into the Hall of Fame. In January 2019, it’s likely Mariano Rivera will be unanimously inducted into the Hall.

Just a few weeks ago, a dynamic player many teams had coveted was traded. Now, he has a chance to establish himself as one of the better players in the American League. Maybe even merit Hall of Fame consideration in 10 or 15 years. If his Hall of Fame fantasies come true.

The Oakland-Tampa Bay-Texas Troika

Jurickson Profar was the player traded by the Texas Rangers. A sleek, swift, 25-year-old, he is now projected as the starting second baseman for the Oakland Athletics.

Profar had an excellent 2018 for Texas, and Oakland undoubtedly sees him as a younger, more exciting version of last year’s incumbent (and now free agent), Jed Lowrie.

Oakland, more than likely, does not view Profar as the same player he was when he first came up with Texas in 2012 at 19 years of age with lofty expectations as one of the best prospects in baseball. He’s now a four-year veteran with something to prove. And if Profar should put up Hall of Fame-like numbers, like a Mookie Betts, Oakland might be shocked, but if he’s above average, that would be more than okay.

That Profar was traded is more about his imminent free agency in two years, than Texas’ dissatisfaction with his play. Because Scott Boras represents Profar, Texas might feel they will be unable to sign him after the 2020 season. So, they moved him now while they can acquire a controllable asset with upside, in return.

Burke Brock is the young, hard-throwing lefty coming off an excellent season in Tampa Bay’s minors, that Texas coveted. Now, he’s Texas’ controllable asset.

For their participation in the three-team trade, the Rays received a 27-year-old right-handed relief pitcher from Oakland, Emilio Pagan, who had a decent season in 2018.

Of course, no one knows which team made the better deal, and won’t for years to come. But now the players involved in this deal can aspire to greatness, like a young Mariano Rivera did. They, too, can entertain Hall of Fame fantasies.

To Vote or Not to Vote for Mariano Rivera

A writer for the Worcester (MA) Telegram, Bill Ballou, wrote a recent article: Mariano Rivera not getting this writer’s Hall of Fame vote.

Ballou writes, frankly, “… Mariano Rivera is the greatest closer in baseball history.”

But then Ballou says he will not vote for Rivera’s induction into the Hall. Hmmm.

“Just because something happens at the end of a game doesn’t make it intrinsically more important that [sic] happens at the beginning,” Ballou explains.

Okay. But where Rivera initially excelled, in the seventh and eighth innings in 1996, was not Rivera’s choice, it was management’s. So, Ballou may be right when he says, “The Closer has evolved into a role created to justify a statistic.”

But so what? Hasn’t baseball been about statistics for years? Anyone heard of Sabermetrics?

Terry Francona said, “If the (save) rules were changed, you might start seeing guys used differently.” Probably. But MLB’s shown no inclination to rewrite the save statistic.

The Andrew Miller Effect: Hall of Fame Fantasies

Terry Francona, after all, was the first of the recent crop of managers to use his closer anywhere other than the ninth inning. Of course he had the diabolical left-hander Andrew Miller among his ammunition. Miller’s wicked sweeping curveball and blinding fastball made even the best hitters look feeble.

But Francona was only the latest manager to call on his best reliever in a dangerous situation early in the game. Twenty years earlier, when Joe Torre was Manager of the Yankees, he used Ramiro Mendoza (Mariano Rivera was already the Yankee closer after 1997) as a super-reliever for several years in under the radar long-relief appearances that ended rallies in the fourth or fifth inning, allowing the Yankees to remain close and eventually win more of those games they fell behind in.

Before Torre, other managers innovated. Eddie Sawyer, Manager of the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies was one of those managers. He rode the National League MVP that year, Jim Konstanty, like a horse who almost single-handedly put the Philadelphia “Whiz Kids” in the 1950 World Series. Konstanty appeared in 74 games, threw 152 innings, recorded 16 wins and 22 saves. Of course, Konstanty was never the same pitcher again.

Which is why Konstanty is not in the Hall. One season of fantastic pitching heroics does not make him a Hall of Famer. Had Konstanty been more like Goose Gossage, and excelled over time, he could have realized his Hall of Fame fantasies.

Ballou goes on to say that Rivera “… was great in the ninth inning.”

Agreed.

But Ballou’s further point is if “… Rivera was that great why not bring him with the bases loaded and nobody out in the seventh or eighth? Why not use him as a starter?”

Rivera did not make pitching decisions. He just performed the role assigned him at All-Star levels every year he played major league baseball.

What is Different about Closers?

Ballou says. “… what [closers] do is the last thing you remember about a game.”

But whatever it was that Mariano Rivera did, even if it was the last moment on the field before a victory, or even when he was on the mound for a defeat (as he was at the end of the seventh game of the 2001 World Series won by Arizona), he did it superbly. No pitcher should be penalized because he excelled at the role he was asked to fill.

Ballou mentions that pitchers should be penalized for not throwing a league minimum innings to qualify for the ERA title (as Rivera never did). Then the question becomes what about discounting innings for starters?

To qualify in 2018, a starter needed to reach 162 innings. And even given that embarrassingly low number, only 57 starters qualified in 2018. Baseball America has commented on this trend of fewer and fewer pitchers qualifying for the ERA title. And thanks to Joel Sherman, it can be added that neither the San Diego Padres nor Toronto Blue Jays had even one pitcher who threw more than 150 innings in 2018.

As good as Max Scherzer or Justin Verlander are, they are not Tom Seaver or Jim Palmer. They are not averaging eight innings a start. But they both are members of a very select club: the 13 pitchers who threw more than 200 innings in 2018.

Less is Now More in Baseball

So, to say that less is more in baseball is to acknowledge the new baseball of the 21st century. It’s a cheaper product. No one works as hard today as 50 years ago. No one is pushed as hard. Players can’t bunt. Even hitting the cutoff man seems like a lost art. A lack of fundamentals. You name it, baseball’s lost it. There are no ferocious competitors anymore. Pete Rose. Lenny Dykstra. Even Mike Scioscia, who was as ferocious a competitor behind the plate as he was in the dugout. Not when everyone’s making a bundle doing as little as possible.

How long before half the teams in the league will be seeking a 150 inning pitcher? And then all the teams? Maybe television has a point: Let’s make the game more manageable, cut it to a two-hour, six-inning affair. Then starters can dream of complete games again.

So, when Terry Francona decided to use Andrew Miller whenever he was needed during the 2016 postseason, Francona’s decision not only seemed radical, it was radical. Because such unusual usage made every team rethink not only how they compensated pitchers brought in in nontraditional situations, but whether they should begin to use their best relief pitchers in the fifth inning. Or even the third inning.

The question became, if they’re not closing, do they get closer’s money? Or starter’s money if they throw 162 innings? Does it even make sense to think of starters anymore? While openers have been pooh-poohed by some, have we arrived at the inverse of the beginning of baseball when instead of one pitcher to throw nine innings we need nine pitchers to pitch nine innings? The Steve Carltons are already dinosaurs, but will Jacob deGrom, Jason Verlander, and the few others like them soon follow? Who will be the future Hall of Famers? One-hundred inning pitchers?

So, $$$, $$$$ and $$$$$

No matter what narrative dominates baseball today, dollars soothe ruffled feathers on the field, in the front office and the television studio.

But since dollars determine the way pitchers are used, how should teams slot the Andrew Millers, Chris Devenskis and Josh Haders of the pitching world when they crossover categories? Just how valuable are these players?

To use Bill Ballou’s logic, these Swiss Army knife guys should be the pitchers who are paid well because they’re not window dressing at the end of the game. They affect games.

The broader question is when do pitchers stop being Hall of Fame candidates because they’re not throwing enough innings for an ERA title? What is the value of a 156-inning starter like Masahiro Tanaka? When do writers like Ballou say there should no longer be any pitchers in the Hall because none of them are throwing enough innings to affect a game? Is 150 the magic number? Or fewer?

Is the day coming when even Sandy Koufax wouldn’t be a Hall of Famer because he was only the best, most dominant pitcher in the majors for six consecutive years?

Or will Ballou decide that Jurickson Profar will never be a Hall of Fame player because Texas misused him his first four seasons when he wasn’t ready to put up big numbers? Or maybe it’s Profar simply wasn’t ready for the majors at 19? Who’s to say? Ballou?

To be fair to Ballou, he opted not to cast a ballot this year, meaning Mariano Rivera can still be the first player unanimously voted into the Hall on January 22, 2019. But there’s no excuse Bill Ballou. Mariano Rivera is a first-ballot Hall of Famer. There is no argument against. Period.