How Baseball Lost Itself: A Tragedy

Between the time Keith Hernandez broke in with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1974 and his last year in baseball in 1990 with the Cleveland Indians baseball lost itself.

Between the time Keith Hernandez broke in with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1974 and his last year in baseball in 1990 with the Cleveland Indians baseball lost itself.

The average baseball salary was $44,000 in 1975. Nolan Ryan hit $1 million in 1979, and George Foster saw his salary offer doubled to $2 million in 1982. These numbers were eclipsed by Kirby Puckett, who signed a $3 million a year contract in 1989. Seven years later, Albert Belle had signed the first $10 million dollar contract in 1996. So, 20 years after the demise of the Reserve Clause, players found themselves in the Wild West of compensation. Lots of home runs, lots of strikeouts and even more money.

During these years, home runs began to rise, pitching-usage changed, strikeouts increased and, by the end of the 1980s, Dennis Eckersley became the first one-inning closer, beginning the specialization of pitching.

The wormhole had appeared and, seemingly, everyone in the game became mesmerized by the wiggle and allure of all the money hidden in plain sight as television revenues grew from $80 million in 1980 to $659 million in 1990, an 800 percent increase.

But as more and more home runs were hit, and the popularity of baseball surged through the steroid circus of the ’90s, bigger and bigger contracts were offered to hitters, until the steroid orgasm of the late 1990s and early 2000s drove revenue from television to almost $1.3 billion by 2001, encouraging every team to play in the free agency sandbox and find their own steroid star.

Hoping to match the steroid stars of the late ’90s, Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, Barry Bonds and Rafael Palmeiro drove up baseball’s ratings as they battled it out to see who would be the greatest single-season home run hitter of all time.

And as more and more players took PEDs to dip their toe in the multimillionaire’s club, salaries continued to escalate. From Albert Belle’s $10 million in 1996, Alex Rodriguez earned $22 million in 2001, $7 million more than Kevin Brown the next highest paid player.

Unfortunately, PEDs were like salt, more intensely flavoring the product. Creating many more opportunities for players who had not been home run hitters before. And fans liked that. Lots of home runs. Lots of runs. Lots of eyeballs.

But too much of anything can be too much. Hence, the increasing value of strikeouts and pitchers who missed bats.

To popularize the power shift in baseball, announcers recently began to drone on about launch angles and exit velocities, numbers that further sanctify the home run. As if it really matters how far a ball is hit or what its angle is. Who cares? As long as it crosses the fence, it’s a home run. Regardless, these phrases are now overused, as if by themselves they can make home runs more interesting than they are. A home run around the Pesky Pole in right field at Fenway is as beautiful as a shot over the ivy at Wrigley Field or one that lands in the water outside the ballpark in San Francisco.

And so it started. A viral infection coursed through the wormhole, infecting everyone in the game with a pernicious scheme that rewarded powerful individual achievement. Not the little things required to win baseball games. Nope. Isolated statistics. And with this lunacy, the multimillion-dollar annual salary was established as the new currency of the post-Reserve Clause era. As baseball lost itself.

In the space of Keith Hernandez’ career, free agency changed the rules of compensation. Ownership realized they could have what they wanted if they wanted it badly enough because all that stood between them and a player they coveted was money. And what did money mean to a billionaire or someone who’s net worth was hundreds of million dollars?

So, owners bickered with each other, unfettered by the Reserve Clause, which had restrained their acquisitive instincts. And to add fuel to their fire, player agents played them off against each other, driving up prices for all players.

But soon the question became, which players were worth the money, and how could ownership be certain? The short answer: That question would not be answered for almost half a century. Just look at all the swings and misses.

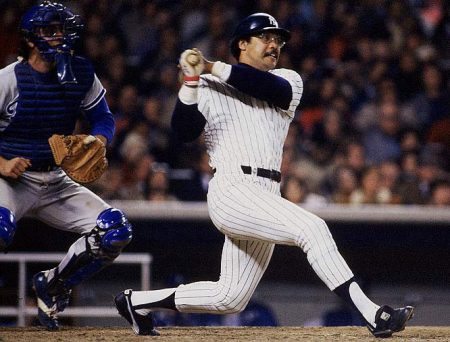

Take Reggie Jackson

The Yankees did. He was one of the first big free-agent signings after the fall of the Reserve Clause (signed by the Yankees in 1976 for five seasons) and his first two seasons in New York, the Yankees won the World Series in 1977 and 1978.

The Yankees did. He was one of the first big free-agent signings after the fall of the Reserve Clause (signed by the Yankees in 1976 for five seasons) and his first two seasons in New York, the Yankees won the World Series in 1977 and 1978.

Soon enough, every owner wanted his own Reggie Jackson. Not Keith Hernandez. They wanted Jackson’s 563 home runs over his long career, even though he never threatened Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record, and never hit more than 41 home runs in a season.

Yet Jackson became known over the years as a clutch performer who routinely delivered so many key hits in big moments that he began to be called Mr. October—partially because he was an important contributor on five World Series winners. He also was an American League MVP, and of course, elected to the Hall of Fame. He was always a lot more than a home run hitter.

Branch Rickey, who frowned upon paying any players big money for statistics that had nothing to do with winning championships, would have wanted Jackson on his team. He was a winner. Period. Made others around him better, despite the occasional histrionics.

While Jackson was one of the first great players to hit free agency, he soon became an anomaly. Teams that understood the new game gradually re-signed their best players before they could hit the market.

So for every Reggie Jackson, 20 Ed Whitsons, Mike Hamptons, Richie Sexsons and Milton Bradleys swamped the market. Were they worth a try? It’s only money, right?

More astute management culled through players in a discriminating way. Avoided the swamps. Found ways to uncover hidden gems and trawled every farm system for quality.

And then there were teams who continued to sign one free agent after another, with dismal results. The New York Mets and the California now Los Angeles Angels are two teams that stand out. Some of the culprits: Bobby Grich. Jason Bay. Bobby Bonilla. Albert Pujols. George Foster. Kazuo Matsui. And Josh Hamilton. There were many others.

A more effective method had to be developed. It was. It was called statistics. Bill James began talking about what he called sabermetrics in the 1980s, not that many people listened at first. But a quarter-century later, team executives began to pay attention, and the Boston Red Sox hired him as a Consultant. And suddenly, a new language of player evaluation was developed. But was this the reason the game atrophied?

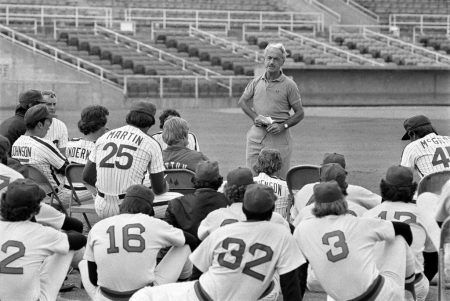

Marvin Who? Marvin Miller

The MLBPA (the players’ union) was expertly advised and guided by Marvin Miller, its Executive Director, from 1966 until he retired in 1983. He taught the players how to organize as one, how to negotiate with ownership, how to demand significant benefits and secure seven-figure paydays (and more). To achieve these ends, Miller guided players through several labor actions, including strikes and lockouts. He not only successfully outfoxed the owners despite their efforts to limit player gains, he broke the Reserve Clause, revolutionizing the game.

The MLBPA (the players’ union) was expertly advised and guided by Marvin Miller, its Executive Director, from 1966 until he retired in 1983. He taught the players how to organize as one, how to negotiate with ownership, how to demand significant benefits and secure seven-figure paydays (and more). To achieve these ends, Miller guided players through several labor actions, including strikes and lockouts. He not only successfully outfoxed the owners despite their efforts to limit player gains, he broke the Reserve Clause, revolutionizing the game.

Yet, somehow, he’s never made it into the Hall of Fame, where he surely belongs.

But by 1983, Miller was gone, and the players’ leadership lost sight of the bigger picture under Ken Moffett, and then Donald Fehr who followed Moffett. The MLBPA would never be as powerful again. More importantly, when the players needed solid advice and guidance in the 1990s, the MLBPA had their eyes closed. Dreaming of home runs and fat paydays. Not steroid addicted players.

By its passivity, the MLBPA allowed ownership to define the contours of greatness and what baseball should value. And by extension, steroid use accentuated the players’ ability to deliver what ownership valued most. Home runs and strikeouts.

And as these changes unfolded into the 1980s and 1990s, baseball began to move in a different direction. Away from the great hitters who did more than just clout home runs, hitters like Hank Aaron, Willie McCovey, George Brett and Ken Griffey, Jr. to more one-dimensional hitters who were either feast or famine. Home runs. Walks. Or strikeouts. A few of these feast-or-famine types were Dave Kingman, Rob Deer, Greg Luzinski, Bob Horner and Jose Canseco, with many others on deck. And with every lucrative contract, ownership sent a loud and clear message about what mattered, to them.

On the pitching side, big changes were also afoot. By 1980, Steve Carlton would be the last starter to throw more than 300 innings in a season. He threw 304 innings in 1980 and no other pitcher has cracked 300 innings since.

From the 1980s and beyond, starters threw fewer and fewer innings every season, until the past 20 years, when most ordinary starters no longer threw enough innings to accumulate 200 innings per season. Some could not even muster enough fortitude to pitch the five innings required to qualify for a win. And all because the numbers clearly showed that most ordinary mortals were not as effective recording outs the third time through a batting order, as the first and second time.

So, teams today carry 13 or 14 pitchers on a 25-man roster to pitch all those extra innings starters used to throw. These hulking monsters trudge out of the bullpen, throw fastballs through brick walls, and strike out the equally robust sluggers poised to demolish the first mistake.

There are now so many pitchers and fewer position players on rosters that managers are in the untenable position of managing a game with only three or four bench players, one of whom must be a backup catcher, usually the last player off the bench. This effectively ties a managers hands at key moments when games are on the line.

So much so, that in some National League games, pitchers now pinch-hit for other pitchers. Pitchers across the game are routinely asked to pinc-run. A few can even play the field. A few.

If this trend continues, there will be more Shohei Ohtani types, like Brandon Woodruff of the Milwaukee Brewers who is pitching and hitting well for the Brewers so far this season. Others will soon follow in Ohtani’s and Woodruff’s footsteps who can pitch, hit and play the field, becoming the new gold standard of baseball players. Players the manager can ask to do almost anything. And they may be the newest beneficiaries of baseball’s gluttonous pursuit of excellence. Unless, like Ohtani, Tommy John strikes them down for a season. Or the National League adopts the DH. (It’s about time.)

Why is Keith Hernandez so Important?

Over a 17-year career, Hernandez never once reached 20 home runs in a season. He swatted only 162 in his career. He was old school, a winner, a team player who did all the little things right and an integral force on two World Series champions: the ’82 Cardinals and ’86 Mets.

A .296 lifetime hitter, he smacked the ball from foul pole to foul pole and won the National League batting crown with a .344 average in 1979, the same year he won the MVP. And he was awarded 11 gold gloves at first base. Many considered him a second manager on the field. He was always in the game.

Hernandez was the Cardinal’s unheralded first pick of the 42nd round, in the 1971 baseball draft, number 776, selected straight out of Capuchino High School in Millbrae, California. He was more than likely selected late because he didn’t run fast, hit home runs and played first base.

So, not much was expected, and the Cardinals might have selected him as a body to play in Memphis, their Triple-A affiliate. Except he surprised them, received his first cup of coffee in 1974 and, by 1976, was the regular Cardinal first baseman and would remain there until his trade to the New York Mets in 1983.

He was the first big piece of the New York Mets’ championship aspirations. A steal by Frank Cashen, the General Manager of the Mets. The same Frank Cashen who along with GM Harry Dalton in Baltimore picked the pockets of the Cincinnati Reds and stole Frank Robinson out from under them in broad daylight, for Milt Pappas and two unforgettables. Robinson becoming the lynchpin of Baltimore’s 1966 and 1970 World Series champions.

Hernandez was not the prototypical new baseball player. Why the Cardinals traded him for Neil Allen and another pitcher, neither of whom ever amounted to anything, was never clear. Rumors of drug use wafted across the New York press at the time though they were never proven. Regardless, Hernandez became the captain of the Mets’ ship. And during his seven years with the Mets, he was easily one of the finest players to ever don the uniform.

Perhaps most important, Hernandez never used steroids. Steroids that were already worming themselves into the soul of the game and beginning their perversion of the national pastime. He simply offered a sharp, measured approach to every at-bat, to every fielding play, game in and game out, his entire career. Hard, honest and passionate.

The Dark Forces Bedeviling Baseball

But performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs), such as anabolic steroids and human growth hormones, those awesome bioactive chemicals changed the rhythms of the game after they were adopted as early as 1982 by some players. Their greatest adoption came by the mid-1990s, though the Mitchell Report (per Section D of the Summary, pg SR-14) acknowledged 1988 as the beginning of the era.

But performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs), such as anabolic steroids and human growth hormones, those awesome bioactive chemicals changed the rhythms of the game after they were adopted as early as 1982 by some players. Their greatest adoption came by the mid-1990s, though the Mitchell Report (per Section D of the Summary, pg SR-14) acknowledged 1988 as the beginning of the era.

Labor problems surrounded performance enhancing drug use, as MLB could not counter the the influence of PEDs without the consent of the MLBPA, which had to be secured through a negotiated settlement. But the players struck on August 12, 1994, and did not return until April 2, 1995. There was no World Series in 1994, and MLB and the MLBPA lost an estimated $1.3 billion.

So, as much change as the game was going through, the game found stability from an old friend, the New York Yankees of the late 1990s, who won four World Series championships with less of a home run hitting team than a small ball team with power. A team personified by Paul O’Neill and Derek Jeter, both of whom played on five World Series winners in their careers.

It was as if the Yankees offered a blueprint for alternative success, and some teams followed that model, while others carved out their own successful plans. The San Francisco Giants won three World Series championships (2010, 2012 and 2014) based on successful pitching and the superb left-handed trickery of Madison Bumgarner.

So, the question here is, were the growing incentives to players in terms of rising baseball salaries directly tied to the growing use of steroids in the mid 1990s?

The players who did bulk up with widely available chemicals enhanced their bodily strengths and produced unexpectedly big numbers, in a numbers-crazy sport. What used to be a once-in-a-lifetime number now seemed within reach of many players. Especially after the Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa carnival of 1998. Admittedly, that competition caught the imagination of America that had yet to understand they were witnessing a steroid circus gone wild.

More than 70 home runs was the next barrier, and Barry Bonds didn’t wait long, clubbing 73 home runs in 2001 while earning $10.3 million, a huge salary for that era. All of it was amazing, except it wasn’t amazing. It was cheating. False news. And it wasn’t only hitters.

Roger Clemens threw hard and struck out hitters into his late 30s, remaining as dominant as he was in his 20s. Allegedly because of steroids, which Clemens still vehemently denies. Yet no other pitchers excelled at the age Clemens continued to excel at. The same was true for Bonds. Statistics speak for themselves.

So, even though only 13 hitters clouted more than 40 home runs during the 1980s, the tone was set for the coming steroid decades when those numbers would be broadly eclipsed during the power-hitting extravaganza of the 1990s and early 2000s when the single-season home run record was surpassed six times after it had taken 34 years for Roger Maris’ 61 homers in 1961 to break Babe Ruth’s old standard of 60 set in 1927.

Specifically, 40 or more home runs were belted 77 times in the 1990s and 91 times the first 13 years of the 21st century. The tone was set.

Powerful hitters like Mark McGwire and Jose Canseco were in demand. Big, strong monsters who could change the outcome of games with one swing. Leading to the Aaron Judges and J.D. Martinez of today’s game.

So, everyone began to juice up, swing for the fences and the huge paydays that went along with those accomplishments. Baseball would never be played the same way again.

And as players swatted more and more home runs over the fences, bigger contracts followed, and a message was sent to every player about what really mattered to the front office.

And the Result of All This Tomfoolery?

Baseball today. A game that lacks creativity. A boring, monolithic exercise that depends on home runs to generate excitement since there’s little patience for slap hitters and the cantankerous types like Ty Cobb, Billy Martin, Eddie Stanky, Pete Rose and Lenny Dykstra, among others who characterized the game years before at the plate, injecting elan into the crowd with enthusiasm, hustle and an infectious passion for the game.

But small ball is not practiced in today’s baseball. And players who do not hit for power are not taken seriously. The Yankees released a good luck charm this past off season. Ronald Torreyes. Injured most of 2018, he was an integral part of the Yankee team of 2017 that lost to Houston in game seven of the ALCS. He homered three times in 2017. That was not his game. But he had clutch hit after clutch hit and he proceeded to bounce around before settling with Minnesota. He clearly was an effective, winning player—at bat and in the field. But despite his pedestrian salary, the Yankees moved on.

Even the great Rusty Staub, a superb outfielder for many years before becoming the pinch-hitting extraordinaire for the New York Mets at the end of his career, would not merit a roster spot in today’s game. Not versatile enough. No matter how much he could hit. It’s debatable if he could’ve been a DH in the American League today. And Le Grand Orange, as fans called him in Montreal when he played there, was not only a threat at the end of his career, but he was pure electricity at key moments in the game, from the first moment he poked his orange-ness out of the dugout and stepped into the on-deck circle.

Even the great Rusty Staub, a superb outfielder for many years before becoming the pinch-hitting extraordinaire for the New York Mets at the end of his career, would not merit a roster spot in today’s game. Not versatile enough. No matter how much he could hit. It’s debatable if he could’ve been a DH in the American League today. And Le Grand Orange, as fans called him in Montreal when he played there, was not only a threat at the end of his career, but he was pure electricity at key moments in the game, from the first moment he poked his orange-ness out of the dugout and stepped into the on-deck circle.

That’s why baseball is in trouble. And pitch clocks and limiting mound visits and moving the mound back two feet will not make the game whole. None of these time-saving ideas matter if the game is not thrilling.

Action-packed games make a difference.

The sixth game of the 1986 National League Championship series, that the New York Mets would win 7-6 in 16 innings, was one of the most exciting games ever played. For six hours, I was glued to the television screen. By the top of the 9th inning, Houston still led 3-0. Then Lenny Dykstra led off with a triple into the right-field corner and the Mets were in business and soon the game was tied 3-3 after nine.

The only home run hit in the game was by Billy Hatcher, not a home run hitter, and it tied the game in the bottom of the 14th inning, 4-4. Otherwise, balls were put in play, runners chased round the bases, and the suspense was excruciating. [In all fairness, I was a Met fan (still am).] For pure excitement, this game had everything. It’s the kind of game baseball needs more of. Needless to say, Keith Hernandez was smack in the middle of the Mets’ victory, doing all the little things to win.

The little things. The old adage, the plays that don’t make the boxscore are so important. They help win games. Moving runners along. Hitting sacrifice flies. Beating out a double-play ball to score a run. And more. Someday, ownership will understand these plays are where their money should be spent. Perhaps they’ll see they’re paying for the wrong metrics.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Did the MLB fail to act during baseball’s steroid era?

Cameron Mee

RoarGuru.24August2014

https://www.theroar.com.au/2014/08/25/did-the-mlb-during-baseballs-steroid-era/

A Brief History of How Steroids Destroyed America’s Pastime

Kyle Watt

BleacherReports.12February2009