Remembering 9/11

I used to think it was weird when older people said they remember exactly where they were when Kennedy was assassinated. How could something that happened to someone else, and that was so far away from almost everyone, have such a lasting effect on people? But 17 years later, I can still recall with unusual clarity the morning of September 11, 2001.

I used to think it was weird when older people said they remember exactly where they were when Kennedy was assassinated. How could something that happened to someone else, and that was so far away from almost everyone, have such a lasting effect on people? But 17 years later, I can still recall with unusual clarity the morning of September 11, 2001.

The day started off like every other around that time. I was cocooned in my comforter in my near pitch-dark room. My alarm clock went off, pleading with me to get up from an insufficient night’s sleep and go to work. Back then, I needed two alarms. The first was just a rock radio station to ease me slowly into the discomfort of being awake, and the second alarm sounded 10 minutes later to put an end to any idea of sleeping in.

That morning, the radio station wasn’t playing any music. But that wasn’t too weird. The Morning Zoo Crew™ was usually blabbering on about something. This was often more effective than my second alarm at getting me out of bed. However, there was a different tone to how they were talking, so I listened.

Two planes had hit the two towers of the World Trade Center and they collapsed shortly after. One plane had crashed into the Pentagon. A fourth plane had crashed in a field in Pennsylvania. I was in Los Angeles, 2,800 miles away and it was almost noon Eastern Time. It was all over. But how could any of this be true? How could it be that these things had actually happened? This radio station was prone to doing pranks. They once switched their music format to disco for a whole day. Hilarious. But that was for April Fool’s Day. And this story was not funny.

I went into work, still hoping that maybe the stories were inaccurate. How could there be inaccuracies in two buildings collapsing? I don’t know—I guess I just wanted there to be inaccuracies.

I was the last into the office (as usual), and seeing the looks on everyone’s faces, I finally accepted that it was real. Nobody worked. Nobody wanted to work. Clients weren’t working. We just watched the news for hours on the television that we had set up a few months earlier so we could watch that summer’s NBA playoffs during a massive project.

It was all so frightening. We felt safe enough since we were in a two-story building. But we kept looking out the windows at the high-rise office buildings nearby. Surely those people were scared.

I only had one friend in New York City at that time, and last I had heard, his wife worked in the World Trade Center. When I finally got hold of him, he assured me that he and his family were safe and that his wife had actually gotten a job further uptown a month before.

An ex-girlfriend of mine called me to make sure I was safe. Her phone hadn’t been working and she was going crazy trying to get a hold of me. She knew that I went to New York and Boston almost every year and that I regularly took early morning flights similar to those involved in the attacks. I had actually been in New York the September before and decided to finally get touristy—going to the top of the World Trade Center. That thought kept bouncing around my head. I had just been there. And now it was gone.

That’s where the clarity of the day ends. I have no idea what I did after I left work or who I saw or what I ate or what I watched on television. I probably watched the news, right? That seems like the thing we were all doing.

There were baseball games scheduled for that night. They were postponed. They had to be—for everyone’s safety and out of respect for the victims of the tragedy. I vaguely remember thinking that I understood, but on a day like that day, watching a baseball game would have been nice.

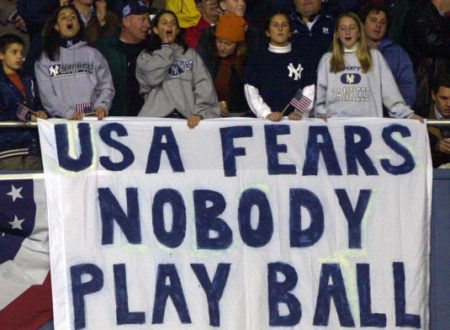

In the wake of any disaster, there is a sense among people that we should all be nicer to each other; that we should be grateful for what we have; and that we should be mindful of those who have suffered. The 9/11 attack was worse than anything most of us could even imagine. And afterward everybody loved everybody. We were all much more like the people that we wished we could be.

When baseball returned to action six days later, they were just games. But the fact that there could be games again was comforting for many – including me. And, of course, we all rooted for our favorite teams, but winning or losing didn’t matter so much as just watching those guys run out onto the field and keep us distracted from our national heartache.

The season ended a week behind schedule. Some people thought the games from that week should have just been deleted. But I was glad they played every single one of them. There was already going to be so very much that reminded us of that terrible year – we didn’t need a strange statistical asterisk popping up every now and then to jar our memories.

When the playoffs came around, a very strange thing happened. Sure, there wasn’t the usual sports hatred between teams, but it was as if all rivalries were put on hold. I’ve been a Red Sox fan since I was a teenager, and my grandfather regaled me with story after story of the team he loved and the players he had spent his entire life cheering for. Part of being a Red Sox fan is hating everything about the Yankees. I liked this aspect of being a Sox fan—I was good at it. I love the city of New York. Heck, it’s where I live. But when things weren’t going well for the Red Sox, I could always hate the Yankees a little and feel better.

In the fall of 2001, I just couldn’t bring myself to hate the Yankees. They had already won four World Series Championships in the previous five years, but we had all had our memories shortened and there was no city in the world that needed a championship like New York City did that year. They pushed through the playoffs and it was very strange for me to not be rooting against the team I had despised for so long.

I’m generally considered an a-hole by most people, however, there’s a time and a place for such things. It would be dishonest for me to say I was hoping they would win. That feeling never once came over me. But I never once hoped they would lose. It felt like I was in some weird sports-fan limbo. I actually felt bad for the Arizona Diamondbacks. They were forced into being the team that was trying to defeat the Yankees and the city of New York. And it seemed that the entire country was against them.

It turned out to be one of the best World Series ever. And the games in New York were out of this world with dramatic come-from-behind victories and almost super-human individual performances by players from both teams. When George W. Bush went out to the mound to throw the opening pitch of the first game, there were no Democrats or Republicans or Independents or Libertarians. We were all just baseball fans—American baseball fans—watching baseball live and on television because we have the freedom to. And there was our country’s leader being exactly what we needed—if only for that brief moment.

Yes, the Yankees lost. But in the bigger picture, the “New York Yankees” won—because they helped show the rest of the country that we could move forward and we could go back to doing the things that were normal—our jobs, our friends, our families.

After the attack, we all swore we would be better people. We let people go ahead of us in line at the supermarket and we thought, “I’m glad I could help make this person’s day just a bit better.” We held doors open for people who didn’t even need that done for them and thought, “We are all in this together.” We even gave a pass to the guy who cut us off in traffic and thought, “He probably just didn’t see me here.”

But memories fade. And, like so many New Years’ resolutions, we started to forget that we decided to be better people and we settled back in to our ways. How many guys can cut you off in traffic before you start getting angry again? And why aren’t those guys being better people? Hello! I was clearly in this lane.

This terrible event happened. It struck fear and grief and anger into our lives. The significance of that day has been somewhat trivialized by politicians and others who are trying to push some other agenda or trying to prove they are the most patriotic of all the patriots. These things tend to evolve this way. I hope that when that day is remembered that we focus on it as a testament to our strength by having moved forward.

It would be great to say that the tragedy made us all better people. I don’t think many would agree with that. But I do think that we proved we could be good people if we needed to be. We proved that when the crap hits the fan and the odds are stacked against us, that if we look to our family and our friends and even our neighbors, there will be someone there to help.